Returning informative API Errors

When building an API it’s natural to put most of the focus into building a beautiful “happy path” where nothing goes wrong. Developers often don’t like to consider the failure cases, because of course everything is going to work out just fine, so errors are often not designed with the same care as the rest of the API.

Errors in an API are not just an edge-case, they are a crucial part of the functionality, and should be treated like a core feature to be proudly shared and documented with users. Failing clearly and concisely is arguably more important than any other aspect of API design.

Errors should:

- Be as detailed as possible.

- Provide context as to exactly what went wrong, and why.

- Help humans find out more information about the problem.

- Help computers decide what to do next.

- Be consistent across the API.

HTTP Status Codes

The journey to great errors starts with status

codes. Status code conventions exist to specify what

category of error has occurred, and they are a great way to help developers

make decisions automatically based on the status code, like automatically

refreshing access tokens on a 403, or retrying the request on a 500.

Learn more about HTTP Status Codes, and how to use them effectively.

Application Errors

HTTP status codes only set the scene for the category of issue that has

occurred. An error like 400 Bad Request is generally used as a vague catch-all

error that covers a whole range of potential issues.

More information will be required to help developers understand what went wrong, and how to fix it, without having to dig through logs or contact the support team.

Error details are useful for:

- humans - so that the developer building the integration can understand the issue.

- software - so that client applications can automatically handle more situations correctly.

Imagine building a carpooling app, where the user plans a trip between two locations. What happens if the user inputs coordinates that which are not possible to drive between, say England and Iceland? Below is a series of responses from the API with increasing precision:

A not very helpful error response, the user will have no idea what they did incorrectly.

This message could be passed back to the user which will allow them to figure out how to address the issue, but it would be very difficult for an application to programmatically determine what issue occurred and how to respond.

Now this includes data that can help our users know what’s going on, as well as an error code which let’s them handle the error programmatically if they would like to.

So, we should always include both API error messages, as well as API error codes. Let’s take a closer look at the best practices for each of these.

API error messages

API error messages should be clear, concise, and actionable. They should provide enough information for the developer to understand what went wrong, and how to fix it.

Here are a few best practices for API error messages:

- Be Specific: The error message should clearly explain what went wrong.

- Be Human-Readable: The error message should be easy to understand.

- Be Actionable: The error message should provide guidance on how to fix the issue.

- Be Consistent: Error messages should follow a consistent format across the API.

API error codes

The use of an error code is well established in the API ecosystem. However, unlike status codes, error codes are specific to an API or organization. That said, there are conventions to follow to give error codes a predictable format.

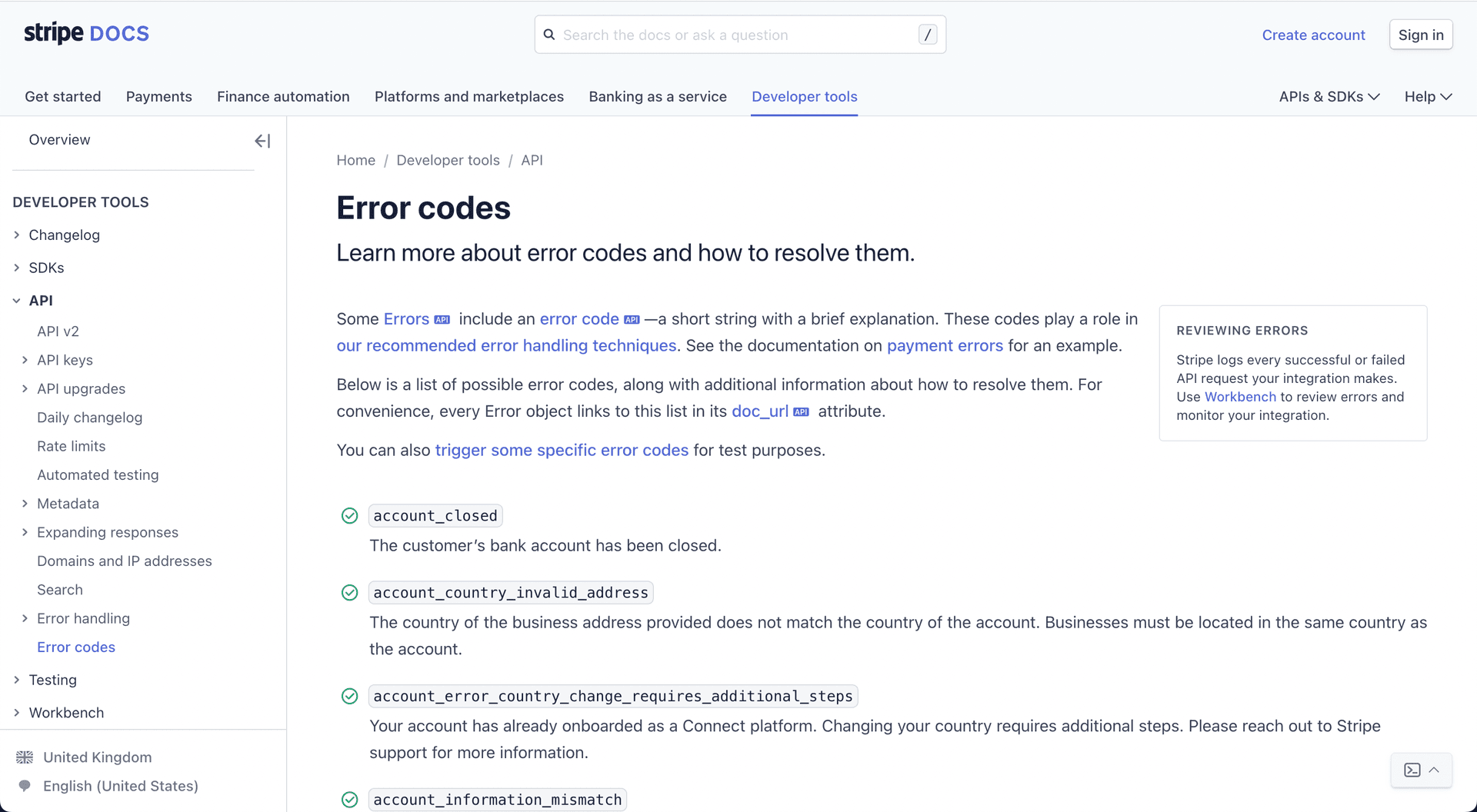

Stripe’s error codes have a nice easy to understand structure. Each error has a code which is a string, and a message which is a string, and that string is documented online so it can be understood, or reported to support.

This makes it easy for developers to react programatically to the error too:

Complete Error Objects

Include a code and a message puts an error message off to a great start, but

there’s more to be done to turn errors into a handy feature instead of just a

red flag.

Here’s the full list of what an API error should include:

- Status Code: Indicating the general category of the error (4xx for client errors, 5xx for server errors).

- Short Summary: A brief, human-readable summary of the issue (e.g., “Cannot checkout with an empty shopping cart”).

- Detailed Message: A more detailed description that offers additional context (e.g., “An attempt was made to check out but there is nothing in the cart”).

- Application-Specific Error Code: A unique code that helps developers programmatically handle the error (e.g.,

cart-empty,ERRCARTEMPTY). - Links to Documentation: Providing a URL where users or developers can find more information or troubleshooting steps.

Some folks will build their own custom format for this, but let’s leave that to

the professionals and use existing standards: RFC 9457 - Problem Details for

HTTP APIs

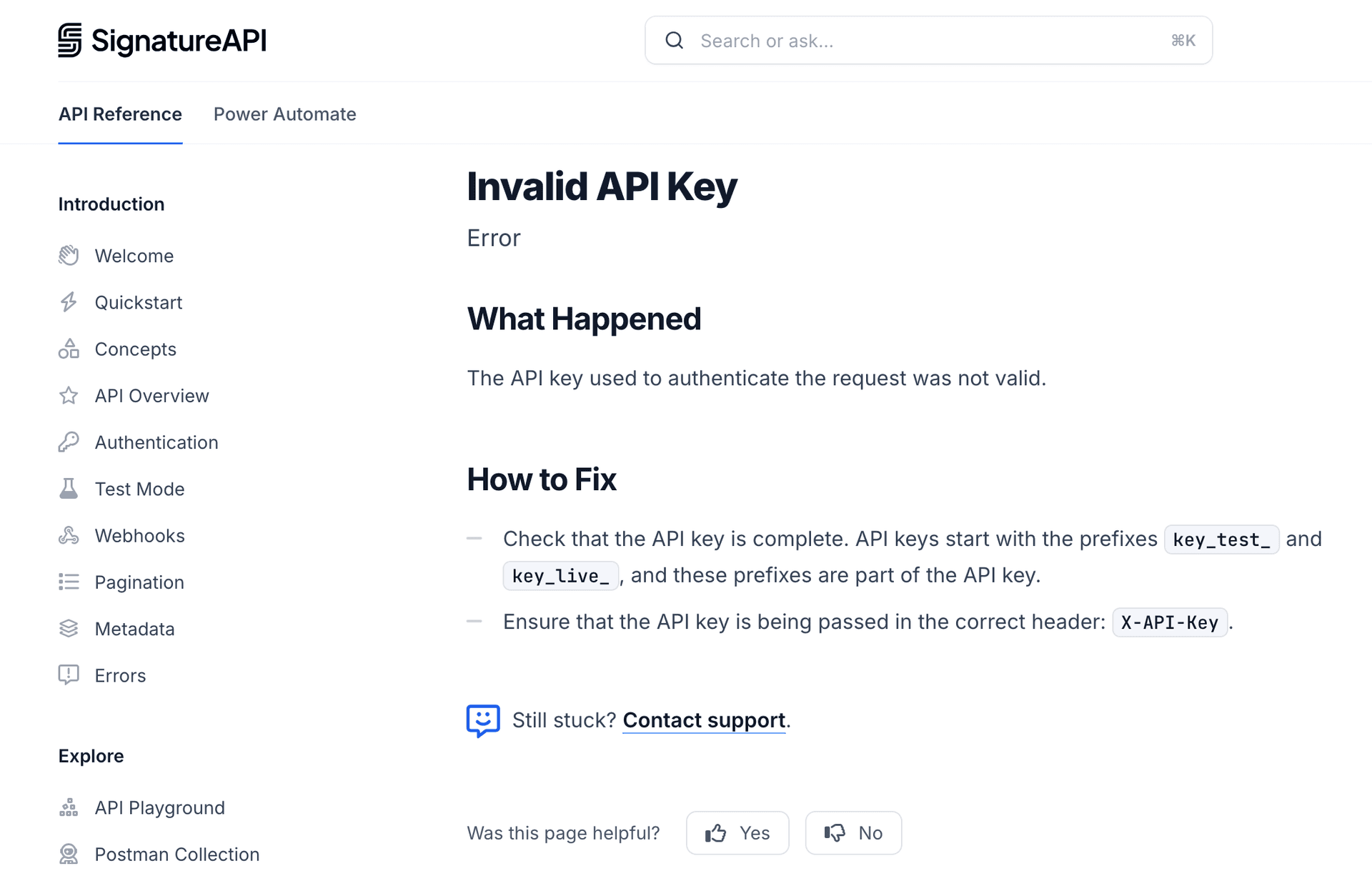

This example of an error from the Signature

API type, which is basically

the same as an error code, but instead of an arbitrary string like

invalid-api-key the standard suggests a URI which is unique to the API (or

ecosystem): https://signatureapi.com/docs/v1/errors/invalid-api-key. This does

not have to resolve to anything (doesn’t need to go anywhere if someone loads it

up) but it can, and that covers the “link to documentation” requirement too.

Why have both a title and problem detail? This allows the error to be used in

a web interface, where certain errors are caught and handled internally, but

other errors are passed on to the user to help errors be considered as

functionality instead of just “Something went wrong, erm, maybe try again or

phone us”. This can reduce incoming support requests, and allow applications to

evolve better when handling unknown problems before the interface can be

updated.

Here’s a more complete usage including some optional bits of the standard and some extensions.

This example shows the same type, title, and detail, but has extra bits.

As per RFC 9457 title (such as "Not enough credit.") should be the same for all problems with the same type

("https://example.com/probs/out-of-credit" in this example),

while the detail can include information that is specific to the

current problem occurrence. In this case, the detail shows the

the attempted debit amount 50 that exceeds the current balance 30.

The instance field allows the server to point to a specific resource (or endpoint)

which the error is relating to. Again URI could resolve (it’s a relative path to

the API), or it could just be something that does not necessarily exist on the

API but makes sense to the API, allowing clients/users to report a specific instance

of a problem with more information that “it didn’t work…?”.

The balance and account fields are not described by the specification, they

are “extensions”, which can be extra data which helps the client application

report the problem back to the user. This is extra helpful if they would rather

use the variables to produce their own error messages instead of directly

inserting the strings from title and details, opening up more options for

customization and internationalization.

Best Practices

Handling errors in API design is about more than just choosing the right HTTP status code. It’s about providing clear, actionable information that both developers, applications, and end-users of those applications can understand and act upon.

Here are a few more things to think about when designing errors.

200 OK and Error Code

HTTP 4XX or 5XX codes alert the client, monitoring systems, caching systems, and all sorts of other network components that something bad happened.

The folks over at CommitStrip.com know what’s up.

Returning an HTTP status code of 200 with an error code confuses every single developer and every single HTTP standards-based tool that may ever come into contact with this API. now or in the future.

Some folks want to consider HTTP as a “dumb pipe” that purely exists to move data up and down, and part of that thinking suggests that so long as the HTTP API was able to respond then thats a 200 OK.

This is fundamentally problematic, but the biggest issue is that it delegates all of the work of detecting success or failure to the client code. Caching tools will cache the error. Monitoring tools will not know there was a problem. Everything will look absolutely fine despite mystery weirdness happening throughout the system. Don’t do this!

Single or Multiple Errors?

Should an API return a single error for a response, or multiple errors?

Some folks want to return multiple errors, because the idea of having to fix one thing, send a request, fail again, fix another thing, maybe fail again, etc. seems like a tedious process.

This usually comes down to a definition of what an error is. Absolutely, it would be super annoying for a client to get one response with an error saying “that email value has an invalid format” and then when they resubmit they get another error with “the name value has unsupported characters”. Both those validation messages could have been sent at once, but an API doesn’t need multiple errors to do that.

The error there is that “the resource is invalid”, and that can be a single error. The validation messages are just extra information added to that single error.

This method is preferred because it’s impossible to preempt things that might go wrong in a part of the code which has not had a chance to execute yet. For instance, that email address might be valid, but the email server is down, or the name might be valid, but the database is down, or the email address is already registered, all of which are different types of error with different status codes, messages, and links to documentation to help solve each of them where possible.

Custom or standard error formats

When it comes to standards for error formats, there are two main contenders:

RFC 9457 - Problem Details for HTTP APIs

The latest and greatest standard for HTTP error messages. There only reason not to use this standard is not knowing about it. It is technically new, released in 2023, but is replacing the RFC 7807 from 2016 which is pretty much the same thing.

It has a lot of good ideas, and it’s being adopted by more and more tooling, either through web application frameworks directly, or as “middlewares” or other extensions.

This helps avoid reinventing the wheel, and it’s strongly recommended to use it if possible.

JSON:API Errors

JSON:API

Pick One

There has been a long-standing stalemate scenario where people do not implement standard formats until they see buy-in from a majority of the API community, or wait for a large company to champion it, but seeing as everyone is waiting for everyone else to go first nobody does anything. The end result of this is everyone rolling their own solutions, making a standard less popular, and the vicious cycle continues.

Many large companies are able to ignore these standards because they can create their own effective internal standards, and have enough people around with enough experience to avoid a lot of the common problems around.

Smaller teams that are not in this privileged position can benefit from deferring to standards written by people who have more context on the task at hand. Companies the size of Facebook can roll their own error format and brute force their decisions into everyone’s lives with no pushback, but everyone on smaller teams should stick to using simple standards like RFC 9457 to keep tooling interoperable and avoid reinventing the wheel.

Retry-After

API designers want their API to be as usable as possible, so whenever it makes

sense, let consumers know when and if they should come back and try again., and if so, when. The

Retry-After header is a great way to do this.

This tells the client to wait two minutes before trying again. This can be a timestamp, or a number of seconds, and it can be a good way to avoid a client bombarding the API with requests when it’s already struggling.

Learn more about Retry-After on MDN

Note

Help API consumers out by enabling retry logic in Speakeasy SDKs.

Last updated on